SciGen Teacher Dashboard

Unit L6

Cells Teaming Up

Conversation: Tricky Transplants

Conversation: Tricky Transplants

Duration: Approximately 75 minutes

In this activity, students learn about the young recipient of a heart transplant and consider the ethics of transplants and tissue sources. The activity ends with an optional philosophical extension with a classic thought experiment.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Students use academic language and scientific facts to support or refute a position while engaging in argument from evidence.

Students write arguments focused on discipline-specific content.

Students introduce a claim about the issue, acknowledge and distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and organize the reasons and evidence logically.

Teacher Tips

- Review the focus words of the week. The focus word chart linked on the unit overview page should be used as a resource for students to review definitions and sample sentences. Encourage them to use as many focus words from this and other SciGen units as they can in their arguments.

- Students may prefer to take one side of the debate or the other. If you expect students will not divide evenly, you may consider randomly assigning them roles or sides in the debate.

- For more videos, readings, and lessons related to organ transplants, visit Go Recycle Yourself or download the curriculum, created by Donate Life Northwest, an organ donor advocacy group in Oregon and Washington.

- Consider pairing this lesson with the comic On Guard — Germs vs. the Immune System in L6.5. It is basically about what the immune system does right, while the organ transplant issues explored below are about what the immune system does “wrong” when organs are rejected by the recipients. The protective qualities of the immune system complicate transplants. The comic can be referred to as you work through this lesson, to explain what is happening at a cellular level in the body.

Teacher Tune-ups

- How are the trillions of cells in a human body able to cooperate?

- How do cells with the same DNA become different?

- What are some practical consequences of the fact that every cell in a human being shares the same DNA?

- Why did some organisms evolve to be multicellular?

- How are cells involved in disease?

Teaching Notes

ACTIVITY OVERVIEW

- Meet Blake, a heart transplant recipient (5 minutes)

- Discuss the video (10 minutes)

- Discuss transplant matching criteria (15 minutes)

- Conversation: Whose heart is it? (40 minutes or more)

- Optional extension: The philosophy of identity and change (10 minutes)

Meet Blake, a heart transplant recipient (5 minutes)

Meet Blake

Discuss the video (10 minutes)

The History and Questions Behind Transplants

The first successful heart transplant happened in 1967. What happened to patients like Blake before that? How might you have felt if you were the parent of a child who needed a heart transplant in 1966? Why?

The heart that Blake was born with needed to be replaced when he was just over two weeks old. Where do you think Blake's new heart came from? Why does it make sense for his new heart to come from a small baby? Do you think it’s ethical to take the heart from a young baby?

Why didn't Blake's immune system reject his new heart? What do you think happened to Blake’s immune system when he received his heart transplant? Why would medical intervention be necessary?

Turn and Talk: What if the President of the United States needed the same organ a 16-day-old boy from Texas needed?

Turn and Talk: What if the President of the United States needed the same organ a 16-day-old boy from Texas needed?

This choice would never happen, because an adult and an infant are different sizes. But if you had to decide, how would you make the call? How about deciding between the President and a single mother? Would it matter how well liked the President is, or how many kids the mother had or the children's ages?

Discuss transplant matching criteria (15 minutes)

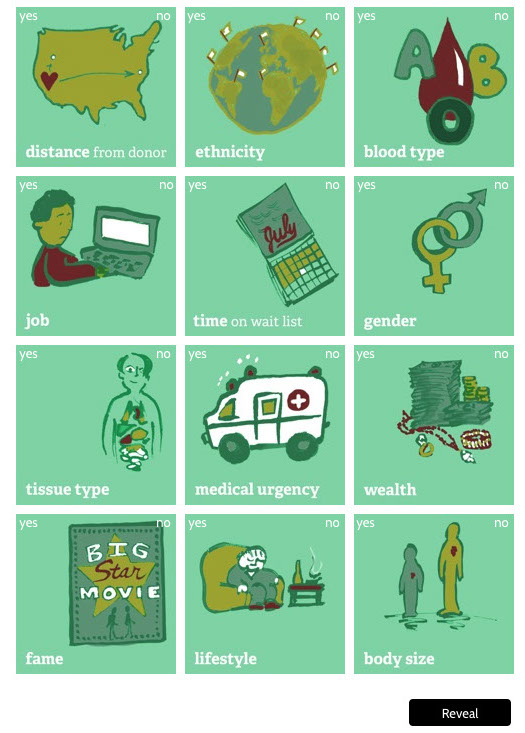

Students choose criteria they think doctors use when adding patients to the waiting list for donated organs.

Paraphrase:

Blake was matched to a donor who died and who was a little over a year older than him. What does it mean to be a match? When an organ becomes available, a computer generates a list of possible recipients ranked according to objective criteria. The top rank goes to the patient whose organ characteristics best match the donor organ and whose time on the waiting list, urgency status, and distance from the donor organ adhere to allocation policy.

Actual criteria:

- blood type: and other tests of the immune system ensure the organ won't be rejected

- body size: a premature infant needs a much smaller heart than a fully grown adult

- distance from donor

- medical urgency: how sick is the patient?

- tissue type: a kidney is not very helpful to someone who needs a liver!

- time on wait list: patients must have a lot of patience; sometimes they can wait years for a match

Criteria not considered (and some challenges you can pose to your students as you cross these off):

- ethnicity (Are we all built the same way? how much do we differ on a cellular level, once the other criteria match?)

- fame (Should it matter how many people care about the celebrity/politician/writer, and how sad so many fans would be? )

- gender (Does it matter if a man has the heart of a woman, or vice-versa?)

- lifestyle (Should we care whether recipients smoke, drink, take drugs, or twiddle their thumbs all day while watching TV?)

- job (What if the person were a teacher? A stay-at-home dad? A powerful executive? A mob boss? A gang member? A criminal?)

- wealth (Surgeries are expensive! Should we check the person's bank account to make sure they can pay for it? If the person has a lot of money, can they pay more to get to the head of the line? Sponsor the hospital's new surgical wing?)

Note that ethnicity is considered for helping narrow down compatible donors in bone marrow matching. It is just more uncommon to match across ethnicities.

For more videos, readings, and lessons related to organ transplants, visit Go Recycle Yourself or download the curriculum, created by Donate Life Northwest, and organ donor advocacy group in Oregon and Washington.

Matching Criteria for Transplants

Who decides which patients get a heart, and why? About twenty people die every day waiting for a transplant. More than 100,000 are waiting for an organ. Think about the typical (median) lengths of times patients wait for a transplant.

- 4 months for a heart or lung

- 5 months for a small intestine

- 9 months for a pancreas

- 12 months for a liver

- 39 months for a kidney

In the year 2000, the United States started using "The Final Rule" to decide the fairest way to assign organs to those waiting for them. Doctors designed a system for ranking patients using six criteria. Which of these 12 criteria would you guess they included and which did they leave out? Use your knowledge of the immune system and how multicellular organisms work to think through the options.

Conversation: Whose heart is it? (40 minutes or more)

Now lead the class in a conversation with multiple viewpoints.

Students may prefer to take one viewpoint or the other. If you expect students will not divide evenly, you may consider randomly assigning them roles or sides in the conversation.

Explain to students:

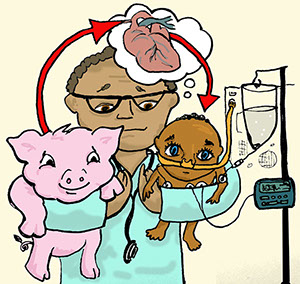

Our class will stage a short debate on whether or not we should genetically engineer pigs to be more useful to humans. No matter how strongly you might feel about an important issue, you will review two perspectives. Understanding another point of view is critical, even if you strongly disagree with it! It is your job to argue well for the position you choose (or are assigned). Use information on this page as well as information from the prior sessions. Is it also a great time to use your previous notes and the unit's focus words; they can help you make a better argument.

For ideas about how to conduct a class conversation, click here.

End this lesson with a general discussion during which students share their own comments and raise their own questions. Note that there are some follow-up extension questions in the next, optional section of this lesson plan.

For more background on xenotransplantation, watch the fast-paced explainer on the topic from the popular YouTube sensation SciShow. This is too detailed for your middle schoolers, but good for a quick backgrounder. youtube.com/watch?v=rq5k3da_UWk

Or you can also read Sarah Zhang's article in The Atlantic: "Genetically Engineering Pigs to Grow Organs for People" (August 10, 2017)

Should we genetically engineer pigs to be more useful to humans?

Human organs for use in transplants are in short supply. Ill patients can wait many years until someone matches their particular chemistry. For more than half a century, we’ve been repairing human hearts with valves from pig hearts. Unlike human organ donors who often die to give the gift of life to a patient in need, pigs are raised specifically to harvest these valves for medical use.

Human organs for use in transplants are in short supply. Ill patients can wait many years until someone matches their particular chemistry. For more than half a century, we’ve been repairing human hearts with valves from pig hearts. Unlike human organ donors who often die to give the gift of life to a patient in need, pigs are raised specifically to harvest these valves for medical use.

Human organs are rejected when the proteins on the surfaces of the cells of the donor and the patient receiving the organ don’t match. Pigs have been genetically engineered so that the valves we collect from them won’t be rejected as often. Some scientists are even trying to find ways to tailor organs to each patient’s immune system, using stem cells.

Researchers have found that pigs are as smart as chimpanzees and as social as dogs... and even cleaner than cats and dogs! Some people keep them as pets. Pigs may carry DNA that could harm humans.

Optional extension: The philosophy of identity and change (10 minutes)

When finished with the activity, ask students to discuss the question with a neighbor before writing creatively about a philosophical paradox.

"The Ship of Theseus" is a true classic when it comes to thought experiments, but the concepts are easy to grasp by even very young students. A much simpler version is "Grandfather's Axe": if you change the handle of an heirloom axe, and then the head, is it still the same axe your grandfather used?

A very readable discussion you can review to prepare yourself for a philosophical discussion about change and identity appeared in the pages of the Utne Reader:

utne.com/mind-and-body/ship-of-theseus-identity-ze0z1311zjhar

The premise stated in the introduction to the Utne article is largely refuted by this video, made by SciShow.

youtube.com/watch?v=ZCiuMomjVx0

This video "Your Body's Real Age" by Skunk Bear, a video producer for National Public Radio (NPR), looks at the lifespan for different kinds of cells of the human body: youtu.be/Nwfg157hejM

For the first slide, paraphrase:

We've talked about transplanting organs to save lives. Our bodies are changing all the time, making trillions of tiny transplants at a cellular level as cells die and get replaced by copies of themselves.

For the second slide, paraphrase:

Think about a ship that is fixed over decades: planks rot and get replaced, the sail gets holes. In the end, no part of the ship is the same as it was when it was first built. Is it the same ship?

Would you still be human if you had a pig's heart?

Are you still you if you have someone else’s heart?

What if you could keep changing your old, worn-out organs for new ones? At what point would you stop being you?

If some of your cells are replaced every day, over time most of your cells will not be the ones you had at birth. Even the unchanged cells may have new materials within them.

So:

Why do we say you are the same person you were when you were born?

BETA Version - Please send comments and corrections to info@serpinstitute.org