Cells Teaming Up (2016 VERSION)

RETIRED BETA VERSION - For current versions of the SciGen materials, please visit serpmedia.org/scigen

Paths of mutual assistance in the hierarchy

In a multicellular organism, the cells all help each other out in a cooperative community. But how? If you pick two cells in your body at random (say, a muscle cell in your shoulder and an epithelial cell in the lining of your stomach), it might be hard to see an obvious connection between them. It’s easier to see how the cells in your body help each other if you look at the steps of the hierarchy through which they cooperate: cell, tissue, organ, system, organism.

Exploring the Hierarchy from Cells to Organism

Cells

A unicellular organism (like a yeast cell, an amoeba, a paramecium) performs all the basic functions it needs to live.

But the cells in multicellular organisms divide up the tasks necessary for the organism to live. The trillions of cells in a human body can be sorted into about 200 kinds. The different types of human cell make different contributions for the benefit of the whole organism. And these highly specialized cells all receive support from each other, to make up for the things they can’t do for themselves. They live through a cooperative division of labor.

Cartoon of a vast crowd of cells. Receding into smaller, more distant images—impression of endlessness, without organization at this point. Maybe labeled, with labels becoming small and illegible with distance.

Tissues

Groups of similar cells join together in tissues to perform similar functions. Tissues consist of similar cells and the materials that surround them. There are lots of different tissues in the human body, and they fall into four main categories:

Epithelial tissues cover and protect structures beneath them. Examples of epithelial tissues include the epidermis (the top layer of the skin) and the inner linings of hollow organs and blood vessels.

Connective tissues join, support, or protect various parts of the body, and sometimes store resources for later use. Examples of connective tissues include bone (which is made of bone cells and the hard, calcium-rich material those cells produce); ligaments that hold bones together; most of the dermis (the layer of skin lying just below the surface layer); and fat tissue, which protects and insulates various structures and also stores energy for later use.

Muscle tissues move things. For example, skeletal muscle moves bones in relation to each other, as when we walk; or sometimes skeletal muscle moves skin in relation to bone, as when we smile. Smooth muscle tissue moves things inside the body, as when food gets swallowed or moved through the digestive system. Cardiac muscle makes the heart beat, pumping blood throughout the body.

Nerve tissues carry electrical signals from place to place, allowing information processing, communication, and control. Nerve tissues are found in the brain and spinal cord, and in nerves that run like electrical wiring throughout the body.

Organs

Tissues are the building materials for organs, which are complex structures that each do one or more jobs for the body. Some organs, such as the skeletal muscles or the brain, are mostly solid. Others, such as the stomach or the intestines, are hollow. Most are hidden inside the body, but the largest organ is the skin.

Each organ does specialized work—the skin keeps water in and germs out, the various skeletal muscles move body parts, the brain processes information and sends conscious and unconscious signals to other organs, the stomach breaks down food, the small intestine pulls nutrients out of digested food, the lungs bring in oxygen and get rid of carbon dioxide, and so on.

As an example of how different tissues combine to form an organ, consider the heart. The job of the heart is to pump blood through the blood vessels that go everywhere in the body. The heart has an outer layer of connective tissue that protects it (and stores extra energy for emergency use in the form of fatty tissue). Next comes a thick layer of cardiac muscle, which does the work of making the heart pump blood throughout the body. The inner lining of the heart wall is made of epithelial tissue; it provides a smooth surface to let blood flow freely through the heart. In addition to this three-layered wall, the heart includes nerve tissue that regulates its beating, and epithelial tissue in the blood vessels that serve the heart (because the heart needs oxygen, just like all the other organs in the body).

Systems

Tissues and organs work together in related groups called systems. The specific jobs done by the different organs within a system add up to a more general service that a system performs for an organism. There are various ways of classifying the systems of the human body; here’s a list of eleven systems:

Integumentary system

Function: Protects the body from the outside world and keeps moisture inside. Helps regulate body temperature. Contains sense receptors for temperature, pain, and touch.

Parts: Skin, sweat glands, hair, and fingernails.

Respiratory system

Function: Inhales oxygen and allows it to be dissolved into the bloodstream. Removes carbon dioxide from the bloodstream and exhales it.

Parts: Nose, larynx, trachea, bronchi, lungs, and diaphragm (the muscle that works the lungs).

Skeletal system

Function: Provides shape, support, and protection to the body, while allowing it to move. Blood cells are also produced in the marrow of bones.

Parts: Bones, cartilage, and joints (ligaments and tendons). Fibroblasts are the main cells in dense connective tissue that makes up ligaments and tendons. Fibroblasts secrete collagen and elastic fibers.

Nervous system

Function: Controls and coordinates body functions. Receives signals, processes information, and transmits responses to organs.

Parts: Brain, spinal chord, and nerves.

Digestive system

Function: The digestive system breaks down food, absorbs its useful substances, and gets rid of the waste. The useful substances—or nutrients—are used by cells throughout the body for energy and building materials.

Parts: The digestive system is made up of the mouth, esophagus, stomach, liver, small intestines, large intestines, rectum, and anus.

Muscular system

Function: Moves the body, moves materials within the body, and generates heat.

Parts: Skeletal muscles, which are attached to bones and move the body around. (Smooth muscle tissue and cardiac muscle tissue are included in other systems).

Cardiovascular system

Function: The cardiovascular system delivers oxygen and nutrients to cells throughout the body. It also carries waste materials away from all the cells. It is also the main distribution system for all sorts of chemical signals, and for white blood cells that travel around the body fighting infectious diseases. The cardiovascular system also helps regulate body temperature, by controlling how much blood flows near the body’s surface at different times.

Parts: The cardiovascular system is made up of the heart, blood vessels, and blood. (Weird fact: blood is considered a connective tissue, even though most tissues are solid.)

Lymphatic system

Function: The lymphatic system takes fluid that has leaked out of blood vessels and returns it to the cardiovascular system. As this lymph fluid filters through the system, white blood cells also check it for signs of infection, and manage the body’s immune response to disease. (Sometimes scientists identify the immune system as a separate system.)

Parts: lymph vessels, lymph nodes, tonsils, thymus, and spleen.

Urinary system

Function: Removes excess fluid and many dissolved waste products from the body.

Parts: Kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra.

Endocrine system

Function: Regulates and controls growth, development, and various body functions by releasing chemical signals called hormones into the bloodstream.

Parts: Various glands throughout the body, including the pituitary, adrenal, and thyroid glands; and also ovaries in women and testes in men.

Reproductive system

Function: The reproductive system produces children through sexual reproduction.

Parts: Vagina, uterus, ovaries, penis, and testes.

read more

read more

read more

read more

read more

read more

read more

read more

read more

read more

read more

Organism

All the systems working together make a whole multicellular organism—in this case a human being. Other multicellular organisms (from mice to mushrooms to maple trees) have different cells, tissues, organs, and systems. Some are more different than others. Mice have hearts and lungs roughly similar to ours. But maple trees have very different kinds of cells, and their organs include things like roots and leaves.

An organism has all the parts it needs to live. A single human cell, or a piece of tissue, or an organ, or an organ system, cannot normally live by itself for long. Those parts depend on each other. Alone, they would die. But the whole multicellular organism, with all of its parts working together, can perform all the basic biological functions it needs to survive.

So can a single-celled organism, like a yeast cell or an amoeba. A yeast cell in a blob of bread dough does not depend on its neighboring yeast cells the way the cells of a human body depend on each other. True, a yeast cell can’t do all the interesting things a human can do. But the yeast cell’s needs are relatively simple, and it is able to cope on its own.

Single-celled living and multicellular living are two strategies for solving the basic problems of how to stay alive:

- storing and following instructions on how to function

- getting energy

- getting building materials

- disposing of waste

All the cells in a multicellular organism need to be able to meet these four basic necessities at a cellular level. Their cooperative organization makes it easier for each cell to meet those necessities. The systems of the organism work together to create an internal environment where nutrients are delivered to each cell for building materials and energy, and where waste is carried away so it doesn’t build up in and around cells.

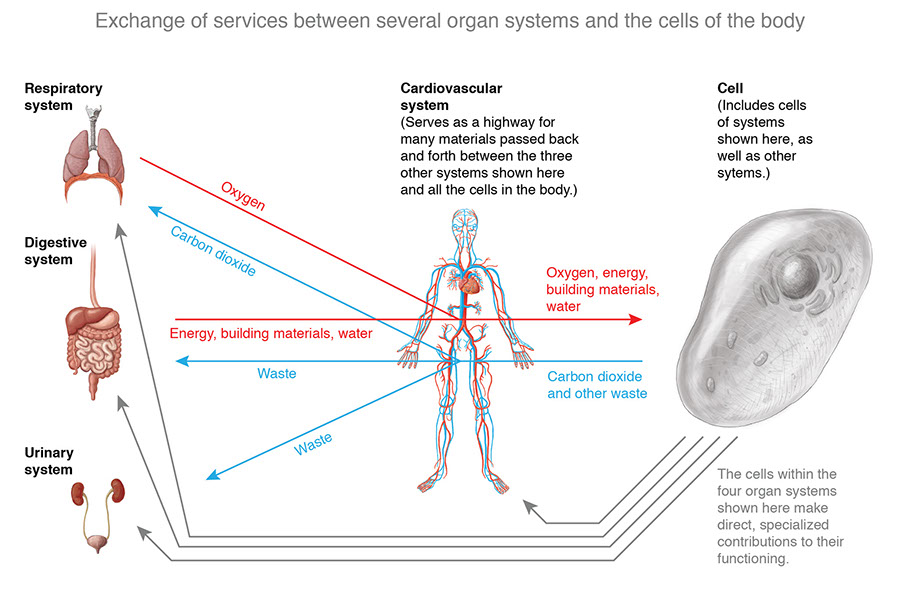

The digestive system breaks down food and absorbs nutrients (and disposes of the unusable portion of food as feces). The respiratory system brings in oxygen for the chemical reactions that get energy out of nutrients in the cells, and disposes of waste carbon dioxide. The cardiovascular system picks up oxygen from the respiratory system and nutrients from the digestive system and delivers them to cells throughout the body. And the cardiovascular system also picks up waste carbon dioxide from cells and delivers it to the respiratory system for exhalation, and picks up waste products from processed nutrients and delivers them to the urinary system for elimination from the body. All of this activity and more is supported by the other systems in the body. (Show nervous system and endocrine system, maybe all, as small peripheral illustrations/icons? with some indication of how they relate to this process.)

Some kind of activity comparing cell function to system function: respiration, digestion, circulation, waste disposal.

Turn and talk: A single yeast cell and a whole human being are both considered organisms. But a single human cell is not considered an organism. Why is a yeast cell an organism while a human cell is not?

© SERP 2017

This Science Generation unit is currently in development. If you have comments or corrections, SERP would love to hear from you! Thank you.